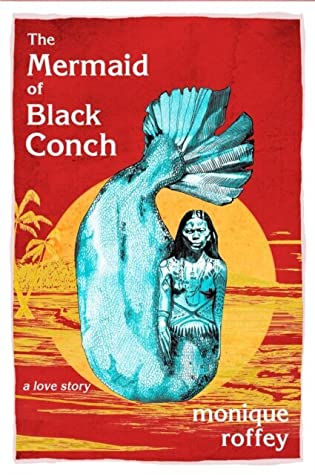

THE MERMAID OF BLACK CONCH – MONIQUE ROFFEY – REVIEW

- edwardwillis6

- Oct 26, 2022

- 4 min read

The Mermaid of Black Conch, Monique Roffey’s powerful 2020 novel and winner of the Costa Book of the Year Award, does what it says on the tin. This is the story of a mermaid hooked in the small Caribbean town of Black Conch, a magical realism tale where a mermaid is caught, turns back into a woman and then back into a fish. Unfortunately, this novel of fishermen and the damaging barbs men cast into women never quite immersed me.

This dark tale has moments to applaud. The relationship between the titular mermaid and a deaf boy is particularly poignant, as well as a clever subversion of the siren trope. In fact, throughout, this book seeks to subvert the mermaid myth. From the Odyssey onwards, Mermaids in literature have called to men, laying spells with their voices that reel men in and draw them to their doom in the waters. It is the same tradition that Disney riffs on when it, Ariel trades her voice for the chance to walk on land. Even in Disney though, it is a woman who takes the role of villain. Here, in the 1976 setting setting, Roffey could not be plainer that it is men who lay the traps. During a visceral opening section which sees two American fishermen pull the mermaid from the water, the author is not afraid to highlight the depredations men perform towards women. The mermaid is instantly dehumanised by virtue of being a fish, a bestialising which permits the men who have captured her to cut her, truss her and hang her up, stand guard over her, fantasise about her, and even piss on her.

The world of Black Conch is not a kind one to women, because it is a world where women, like mermaids are possessions, something to hold. Aycayia is rescued by a local man, David, who takes her back to his house, where her tail drops off and she turns back into a fully-fledged woman. And although he does generally respect her, his behaviour highlights the power of owning, both in his actions (he immediately desires and wishes to marry the mermaid) and in his fears about what other men might do to his mermaid on land. That this is true even in Black Conch, where the major landowner and the powerful local barmaid are both women, reminds us how far the world has to go in this respect. In fact, Roffey reminds us, has the world perhaps even taken a step back. Aycayia, in her life thousands of years ago, was at least cursed by a woman. In the 20th century, it is mainly men she has to worry about. In the current UK context, this has become a timely and enlightening book, reminding us that it’s not the witches and those who are different who we should fear so much as the men who burn them.

Aspects of class and race are foregrounded too. The unstated financial coercion at play in the Americans’ power to control the black crew as they capture the mermaid is uncomfortable to read. More nuanced is the fact that the landowner, Miss Rain, is white, juggling the legacy of slavery as she sits unhappily in her house on the hill, dealing with her own heartbreak at the hands of a man.

Some of the language and metaphor is melodic, and Roffey’s varying perspectives add variation to the novel. The mermaid for example is heard directly in free verse, while her rescuer, David, speaks in the form of a first-person diary that employs a well adhered to Caribbean dialect. A third person limited perspective mops up the rest. At times this works well, at others, it contributes to a slight sense that the novel is a little disjointed, needing to cast off the molluscs and clams from its own structure just as Aycayia needs to cast the remnants of the sea off her body when she becomes a land-dweller again.

On the whole, there was much to admire but slightly less to love. It was hard to shake the sense that there is neither quite enough magic nor quite enough realism to propel this into the top ranks of the genre. Magical realism needs complete commitment and conviction to work. Without it, stories quickly feel shallow. For me, the transformation plot was a little thin, and the central love story a little narrow and Disneyish, even if it was at least a case of the man falling for the first person he meets in the story rather than the woman, even if it did not have a fairy-tale ending. Some of the other characters also felt a little cartoonish, from bile filled father to the bent copper, to the jealous hussy. It felt like a novel that needed at least another 50 pages to grow into itself.

The Mermaid of Black Conch has gathered some rave public reviews as well as critical acclaim. So, although it didn’t quite sing to me, that is no reason to write it off. Some of Roffey’s writing is beautiful and it is, at the very least, thought provoking and moving in places, a timely meditation on the way humans can be turned to violence against anyone who is different. Most importantly of all, it reminds us that in a man’s world, the very act of being a woman can be an act of difference.

Comments