My Favourite Reads of 2022

- edwardwillis6

- Dec 21, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 22, 2022

From books set in uncertain futures to lyrical historical fantasies, books that batter down the traditional borders of crime fiction and books that remind us of the value of preserving our world and our literature, my 2022 has been filled with wonderful books. Narrowing it down to my ten favourites was extremely difficult, but here goes.

Great Circle - Maggie Shipstead

Probably the best book I read this year was also the first book I read in 2022. In this novel, we follow two women built in the same vein, Marian Graves, a daredevil female aviatrix, and Hadley Baxter, the troubled former child star playing Marian in the film of her life. For a novel devoted to the air, obsessed with the magnetic pull of soaring above the clouds, there is an overriding sense of melancholy. Yes, you may fly high, but always, there is the lure of a crevasse, of ocean depths, of dark spaces ready to suck you down. Those dark spaces are even more noticeable in word and deed. There is child abuse, coercive control, alcoholism, and suicide. Throughout the novel in fact it is people, not earth or sky or air or cold or wind that really break people. Men, women, and the wars and betrayals they create are the only thing that break us so deeply that even navigators can’t find a way through. Click here to read full review.

Cloud Cuckoo Land - Anthony Doerr

Quite simply one of the best writers in the business, Doerr's powerful, lyrical novel is his first since the smash hit All the Light we Cannot See. Cloud Cuckoo Land is set partly in Constantinople in the build up to the fateful siege and conquest of 1453, partly in 20th century Korea and Idaho and partly far in the future. And in case those weren't diverse enough choices, the stories are linked by an imaginary novel by the real Greek author Diogenes. Fascinated by that historical moment and by other fictional depictions of Constantinople, not least by the next author on this list, I particularly wanted to love Anna and Omar's stories but arguably found the present and future storylines even more moving. Doerr stitches his disparate tales together in a way that is constantly inventive, heart-warming and inspiring. It's an important story too. As Seymour's rising zeal might just remind us, compared to our other options, the real Cloud Cuckoo Land, the land of plenty, might be Earth itself.

A Brightness Long Ago - Guy Gavriel Kay

I have a growing shelf dedicated to first editions of Guy Gavriel Kay's extraordinary novels, but they are so beautiful that I find myself rationing them. So it is that I only got to 2019's A Brightness Long Ago this year. Kay's genius for writing unlikely friendships in trying times is on full display. This is historical fantasy with an emphasis on the former, and the fantastical moments are understated. Inspired by the Italian wars of the 15th century, the book teems with renaissance politics, art, and violence. There is also a particularly memorable analogue to Siena's Palio. Between this, chariot racing and Sardian horses, there is, I suspect, an essay to be written about horses in Kay's novels. There are plenty of Easter eggs for those who have read Children of Earth and Sky, and though this technically serves as a prequel, either book could be read as a standalone. 2022's follow up, All the Seas of the World has been staring at me impatiently from my bookshelf since launch. As an additional bonus for those who enjoy audiobooks, many of Kay's novels are narrated by Simon Vance. The pair are a perfect combination.

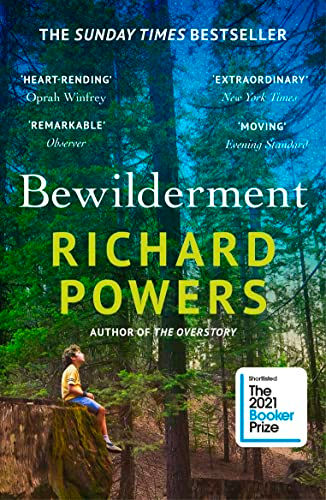

Bewilderment - Richard Powers

I utterly adored Powers' Overstory, which is one of the books I find myself recommending most often. In Bewilderment, Powers again focuses on the heartbreaking breaking of our natural world, this time mixing in some vivid imaginings of life beyond earth. The effect of that imagined proximity to outer space is to highlight just how far away we actually are and how much more urgently we should be investing in the one earth we do know fully. The conceit of setting the story clearly in a near future without giving a precise year is an effective way of highlighting the urgency. This will be us - but is it tomorrow, or twenty years away, or fifty, or a hundred?Bewilderment is also a touching novel about a father and son relationship, with Robin repeatedly drawing a blank as to how to explain mankind's laissez faire attitude to climate collapse to his autistic son. Bewilderment again touches the extremely lofty (think gigantic redwood) heights of Overstory. It is a powerful and beautifully written book, and also perhaps more accessible for those who don't like novels that deal with seemingly disparate characters.

The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle - Stu Turton

Turton's books are just a total blast. Charismatic characters, high stakes, and mind-bending twists are his calling cards and they are present here as in The Devil and the Dark Water, which I also loved. The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle is at once a glorious homage to the golden age of crime fiction and a completely fresh, totally modern take on the genre. The work that must have gone into planning out the character motivations, the timing of which character would be occupied and where they would be when, and the pacing of the revelations must have driven Turton as mad as the situation nearly drives his protagonist. This is intricate, pacy, and totally compelling.

The Golem and the Djinni - Helen Wecker

It is hard to write non-human characters. Helen Wecker manages to avoid the temptation to make them humans with a different face, instead achieving the opposite, human faced characters who think and dream and love completely differently to humans. In fact, it is often a source of regret to the eponymous characters that they cannot perform some of the mundane thoughts or tasks that give meaning to humans. Set in 19th century New York, Wecker manages to craft a page turner by tying the fate of Chava and Ahmed - the Golem and the Djinni - together with that of a charismatic villain hunting for that long-chased pursuit of sorcerers - eternal life . The tenderness of the writing brings to the fore the sense of exile that the characters feel, and of course by doing so reflects on what generations of human immigrants to New York have endured.

Klara and the Sun - Kazuo Ishiguro

Another novel that distinguishes itself thanks to its vision of what it means to be non-human in a human world, and another novel that does not date its future, Klara and the Sun displays all Ishiguro's usual poise, poignancy, and control. Klara is an AF or Artificial Friend, who is purchased by Josie and her Mother and becomes increasingly vital to the family. Written in a well-judged first person, the novel is often at its most compelling when it juxtaposes Klara's extensive coded knowledge with the gaps in her understanding. For all that we can develop AI, Ishiguro reminds, we cannot recreate humanity.

The Appeal - Janice Hallett

This debut crime novel unfolds entirely over email, text, letter and other ephemera. However, if that makes it sound like the last book you want to reach for after staring at your computer all day, don't let it put you off. This is a pacy, unsettling thriller, whose most impressive trick is managing to create three dimensional characters out of fifteen suspects who only ever appear in written messages. Although there's no background narrative to tell us how people move, the way they communicate by email is so distinctive that it becomes easy to imagine. In a small English town, the daughter of a leading local family - in the town's theatre troupe they also habitually take on the roles of literal leading ladies and gentlemen - has been diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. The community comes together to help raise funds for her treatment, but before you can say "all's well that ends well", strife, suspicion and ultimately miurder, come to the party. The novel's conceit is that two lawyers are reading the same documents you are given in order to identify the murderer and free a suspect whom their boss believes to be innocent from prison. That readers are not given the identity of the incarcerated adds another layer of mystery. This is a breezy but intricate novel that deserves applause for its bold approach to crime fiction. I have Hallett's next book, The Twyford Code, firmly on my TBR pile for 2023.

American Dirt - Jeanine Cummins

Some books shake you by the hand and draw you into an armchair. Others punch you in the face and make you feel lucky it wasn't worse. This is one of the latter. American Dirt tells the story of the escape to America of a Mexican woman, Lydia, who is trying desperately to stay one step ahead of the cartel that has murdered her whole family and are still out to find her and her young son. One of the novel's most heartbreaking moments comes when Lydia, a professional woman from a once thriving area of Mexico, realises that she and her son are now something she never thought she would become - migrants. Readers journey with Lydia across La Migra, the infamously brutal route through Mexico where risks are one a minute and respites are rarer than rape. American Dirt is an arresting, intimate novel, as well as a powerful and timely reminder that the push factor away from violence is always greater than the pull of the wealthier nation when it comes to migration.

Matrix - Lauren Groff

Taking the little known and much occluded story of the poet Marie de France as inspiration, Groff installs Marie as the new prioress of a starving, diseased 12th Century monastery in relentlessly grey England. Groff’s Marie is not, at least initially, a devout woman, but rather a lovesick teenager hoping to win a reprieve from the nunnery and the impossible love of the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Painstakingly - often literally - and slowly, Marie will turn the nunnery around, learning to lead the women, secure her position, raise revenues, and fight back against those who would do her community harm. Here is a titan who will be the rock on which her abbey grows, someone adept at harnessing the strengths of her flock. In her prioritisation of the human over the divine, the shielding of her sisters from papal interdicts, she is something of a literary cousin to the Prior Philip of Kingsbridge. Most particularly, the link is present in her relentless pride, something to be both celebrated and censured, for as she builds up her Abbey, Marie will struggle, above all with the question of whether she acts for the good of the abbey or the good of Marie. But Marie is a more cynical, more physical character than Ken Follett’s priest. She ruthlessly undermines an upstart rival, and, for all that readers might expect a book about a nunnery to be fairly bloodless fare, Matrix is a visceral, at times brutal, read. Click here to read full review.

Honourable mentions

How Much of These Hills is Gold - C Pam Zhang

A History of the world in 10 1/2 chapters - Julian Barnes

Lancelot - Giles Kristian

Dark Earth - Rebecca Stott

A bookshop in Algiers - Kaouthar Adimi

Comments