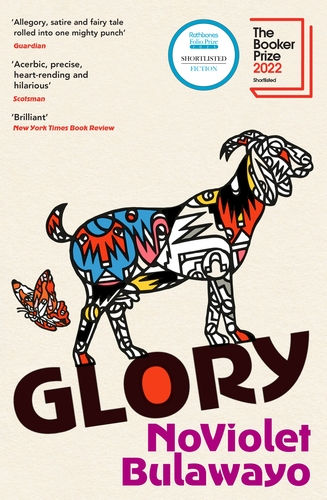

Glory by Noviolet Bulawayo - Review: Cold Comfort on Zimbabwe's Animal Farm.

- edwardwillis6

- Feb 9, 2023

- 4 min read

This darkly comic fable earned Noviolet Bulawayo a place on the Booker Prize Shortlist, but what it offers in blunt force, it lacks in subtlety and characterisation. Based on Robert Mugabe's fall in 2017, but also drawing on global protest movements including the death of George Floyd, Glory is at times poignant and hard-hitting but at others hard to feel at home in.

Slowness is often baked in with prize nominees, but so too is subtlety. And here it is just a little lacking. It would be clear to the most cursory student of international affairs of the last half century that the novel is predominantly about Zimbabwe, that the old horse is Robert Mugabe, and his preening wife is Grace. Another section - where the author provides a full page with no other words than "I can't breathe" - is an obvious analog to George Floyd. But the combination of the mixed origins and the easiness with which the events are parsed reduces rather than enhances the impact. It also opens up occasional jarring paradoxes. Mugabe shouldn't be in this world because he has been replaced by his animal analog, the old horse, and yet we still get R.Mugabe street.

A novel this long and this thought-led needs strong characters to bounce its ideas off, but it doesn't deliver them in a focused enough way. And that's a shame, because

some of writing is stunning. The novel is full of lovely little vignettes that serve to flesh out the world of the novel - often to show the mundane impacts of bad government as well as the fundamental. A particular favourite was an old woman who prefers to let guava rot on her tree out of spite because she has lost her teeth. That one is of the more inconsequential variety but there are other scenes that are genuinely harrowing.

Overall though, the characterisation is frustratingly shallow. This is clearly a deliberate choice - Bulawayo is too talented for this to be an oversight - but it's hard not to think that this would be a stronger novel if it were more character led. It would be easier to feel the full horror of the disappearances, the torture, the election tampering, all the litany of the party of power's crimes if we better knew those they were perpetrated against. I think perhaps this is the point Bulawayo is trying to make - that it is often too easy, from the outside looking in, without those close connections to misunderstand the scale of the abuse. As the famous Stalin quotation goes, "One death is a tragedy. A million is a statistic." It's a powerful and indeed persuasive argument, and I understand why Bulawayo has set up to reinforce it here, but it just doesn't make for a particularly rich novel reading experience.

When Bulawayo does make this a character-led novel, it touches on the compelling. The main bright spark in this regard was Destiny. The young firebrand, a prodigal daughter returning to her heartbroken mother from exile having found trouble abroad too was full of a believable, three-dimensional mix of bitterness, shame, fear and hope that was missing elsewhere. Her chapters were the most coherent and absorbing and they helped prop up what was an effective ending.

However, getting to that ending requires some patience, and the first half of the novel in particular does sag. One reason for this is that the narrator does not shirk in telling readers, right from the beginning of the party of power's heinous crimes, which limits any moments of suspense, mystery, discovery, and characterisation that might have been afforded by a more gradual release of information. Again, I suspect this is deliberate. Bulawayo wants to conjure the crippling hopelessness that comes with knowing the situation, knowing others know the situation, and knowing that there's nothing you can do about it. But, once again, what is a powerful philosophical point is not necessarily best practice for an engaging novel. When you realise that Bulawayo initially planned to write this story as non-fiction, more pieces click into place.

It's a shame because a more nuanced approach would have further illuminated some lovely ideas. Glory makes some stark points about people who pursue power. One particularly affecting moment shows for example the deposed father of the nation in disbelief that cars had not begun crashing into each other now he was no longer in power. Others show just how precarious nations are when the ruling elite consider themselves above the law, something that will feel familiar (albeit to a less disastrous degree) to anyone who's lived through recent UK political history. There are important warnings, and Bulawayo communicates them powerfully.

Glory has been often framed as a Zimbabwean Animal Farm, but in style and plenty of other ways it's far removed from Orwell's spare, creeping classic. Animals being animals doesn't seem to matter here. This is an animal only world, in Jidada and abroad, and so there is no degeneration or evolution into human behaviour as is such a powerful force in Orwell's novel. As a result, the central conceit feels a little contrived rather than a necessary driver of the plot or characterisation. It's a way of distancing the reader and making this general rather than specific, but it risks making it too distant, too general.

More than anything though, this book struggles with repetition. Yes, repetition. I mean, real repetition. Where ideas are presented again. And again. And another time. Then once for luck. Then once more, perhaps stated a little bit differently. Sometimes on a full page. Sometimes chapter after chapter. Repetition, you understand.

The writer uses lists, and litanies, and, tholukuthi, reams and reams of tholukuthis and Jidadas with a da and another da. At times it works, but the emphasis effects it would have are mitigated by the repetition of repetition as a technique.

This overlong book about a struggle is unfortunately a struggle to read, and it is a shame for a book that at times powerfully describes a national and international shame. As a novel rather than as non-fiction or a political statement, overall it just feels like too much readability and plot has been sacrificed to bluntness.

Comments